Cranes with Ultralights, Beaver with Parachutes: Ecological Entrepreneurship Success

By: John A. Baden, Ph.D.Posted on January 14, 2015 FREE Insights Topics:

People observe their surroundings with an implicit model of how the world works. Very few however, even alert individuals, appreciate the scope of ecological entrepreneurship. It's easy to understand those seeking profits: They produce a new product or service and sell it in the market. Motivating incentives are obvious.

Nonprofit entrepreneurs are more illusive and their strategies vary. They find or create new opportunities to improve or preserve something not well addressed in the exchange market. They may do something directly, for example fund research on how we might save an endangered species such as whooping cranes.

In the conservation arena entrepreneurs often cooperate with a wide range of organizations; government agencies, firms, non-profits, and individuals. Examples include the many organizations created to protect wildlife and their habitat. Ducks Unlimited, Trout Unlimited, Pheasants Forever, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and the International Crane Foundation are a few well-known organizations created by environmental or ecological entrepreneurs.

The American Prairie Reserve (APR) may be the most ambitious conservation exercise concocted in the past century. This Bozeman based American Prairie Reserve became a public charitable foundation only fifteen years ago, in November of 2001.

It's goal for over three million acres in North Eastern Montana, an area one and a half times the size of Yellowstone Park, “...is to create and manage a prairie-based wildlife reserve that, when combined with public lands already devoted to wildlife, will protect a unique natural habitat, provide lasting economic benefits and improve public access to and enjoyment of the prairie landscape.”

To accomplish this, it collaborates with over a dozen agencies, other nonprofits, and firms. APR even created one commercial beef firm, Wild Sky to supply high-end restaurants. “When you buy Wild Sky you’re getting more than a great steak on your plate–you’re also helping build American Prairie Reserve, increase wildlife populations, and support our neighbors.” Photos of the ranch families appear on the menus.

The APR demonstration of twenty first century conservation may be the evolutionary successor to the Progressive Era state and federal resource management agencies such as the U. S. Forest Service and the Park Service. I am highly interested in exploring the APR experiment and expect to feature it in my next book.

The private sector has no monopoly on entrepreneurial ecology, but those outside government have far more liberty to innovate. Bureaucrats have strong and persistent incentives to color within the lines. Further, political constraints often thwart conservation goals. Some of the most successful conservation work involves cooperation among agencies, non-profits, private individuals, and firms.

One example is Wisconsin's Onion River, once and now again a productive trout stream. Horse and fish farms had built over two-dozen dams that blocked trout spawning grounds. A private conservationist couple bought the farms, tore out the dams, and gradually sold the properties to the Wisconsin DNR. The river again produces trout and is open to for public fishing. “We like to return wildlife to where it belongs and try to do it without hurting people as a result”. (For an account of this successful saga see: Kamrath Restoration, Onion River Headwaters, Wisconsin Trout Unlimited website.)

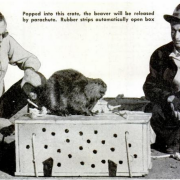

Parachuting Beaver into Backcountry

We can celebrate such success and here is a public sector success to cherish. In the late 1940s beaver were over abundant animals in some areas of Idaho where they harmed irrigation and orchards. (Ramona and I understand this for we have experienced occasional but severe beaver damage on our ranch.) Beaver had been trapped out in some remote areas of Idaho.

As recently demonstrated by their return to Yellowstone Park, beaver make major contributions to other wildlife and watersheds. The Journal of Wildlife Management reported in 1950, “...(beaver) do much toward improving the habitats of game, fish, and waterfowl and perform important service in watershed conservation”.

Understanding this, the Idaho Fish and Game Department live trapped beaver where plentiful and transported them to remote areas. The beaver would be live trapped and trucked to a trailhead. Then they would be packed by mule and horse train to back country meadows. Alas, this was a costly process and created problems for mules and beaver. The mules didn't like carrying squirming, odiferous beaver and beaver mortality was high. Many beaver died from the summer heat while being packed.

Here was a promising ecological improvement, reestablishing beaver, but one with large delivery problems. Some creative individual in the Idaho Fish and Game Department devised a solution in 1948, parachute them in from airplanes. Beaver were placed in boxes that sprung apart upon landing.

To figure out how to do this successfully they experimented with a beaver named Geronimo. They determined that the best release height was from 500 to 800 feet. The parachute would open and the box would open upon hitting the ground. In 1948 they released 76 beaver with only one dying, he fell out of his box when 75 feet in the air.

“This was a savings over mule packing as four beavers could be moved for $30. The experimental Geronimo was among the first group released to the wild, he with four young females.”

(Transplanting Beavers by Airplane and Parachute, Elmo W. Heter, The Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Apr., 1950), pp. 143-147, Published by: Wiley)

While we can celebrate this entrepreneurial effort of the 1940s, today's environment makes such creative ventures by a state agency quite difficult. Imagine the outcry over spending taxpayers' funds to deliver beaver by parachutes. Easy target indeed. Likewise, today's costs would be far, far higher than the per-beaver delivery cost in 1948, only $72 in today's money. Further, the potential protests by PETA or other animals rights groups, and by fiscal watchdogs, would deter politically sensitive agency officials.

Teaching Whooping Cranes to Migrate With Ultralight Aircraft

The whooping crane is one of only two North America cranes. It suffered major population decline from habitat loss and over-hunting. The population declined to 15 individuals in the 1940s and cranes were classified as endangered in 1967.

I heard of its plight when George Archibald, president of the International Crane Foundation (ICF) visited Bozeman years ago. Later I learned that friends of FREE at the Windway Foundation led recovery efforts. Here is the short version. (An account is given in Chasing the Ghost Birds: Saving Swans and Cranes from Extinction by David Sakrison, Watson Street Press, 2008.)

Terry and Mary Kohler helped return the trumpeter swan to Wisconsin by flying to Alaska and bringing trumpeter eggs back to Wisconsin to be hatched by the state's DNR. George Archibald learned of their good work and asked if the Kohlers would make additional trips to northern Canada to collect whooping crane eggs. They did so for six years, delivering the crane eggs to the ICF for hatching. They carried 60 eggs per trip in their custom-made temperature controlled box.

The ICF raised the crane chicks without direct human contact so they would not imprint on people. The next problem was teaching them to migrate. The answer was a series of ultralight airplanes. They were used to lead the birds to winter homes in Florida. After doing it once, the birds know the drill. They return to where born and the migration pattern goes on. Due to crane predation by Florida bobcats, cranes were also led by ultralights to a new wintering area on islands off Louisiana’s Gulf Coast.

Here is a take-away lesson for individuals interested in ecological restoration and preservation. New conservations problems constantly emerge--and so do opportunities. Ecological entrepreneurs arise to bridge the private and governmental sectors. Neither their identities nor their practices can be predicted but we should be sensitive to their potential.

When we see examples, of failure as well as success, it is important to tell the stories. Explaining this process will be the theme of my next research and writing project. As we learned with beaver, cranes, and swans, success can be contagious. An important part of FREE's mission is to foster such conservation success.